ST. LOUIS — Joe knew something was terribly wrong when his wife, an energetic nurse and mother of three, became

forgetful in her early 60s. Four years ago, Lynn was diagnosed with dementia but decided against having a spinal tap

that would have shown whether the cause was Alzheimer’s disease.

The couple chose to pursue a lifelong dream, buying a 40-foot camper and traveling to national parks in 35 states. “It

was an adventure we could have together,” Joe said.

Last year, the couple returned to their home near St. Louis. After contracting covid-19, Lynn became increasingly angry

and agitated. When an anguished Joe asked whether there was anything he could do, his wife’s neurologist at Washington

University in St. Louis suggested a new blood test for Alzheimer’s to rule out other illnesses.

The test confirmed that Lynn, 68, has the fatal neurodegenerative condition, saddening her husband but giving him some

peace. “After 50 years together, she is on a journey of her own, and I can’t go along,” said Joe, who like other

relatives and patients interviewed for this story, spoke on the condition that only middle names be used to protect

family privacy.

Simple blood tests for Alzheimer’s disease, long coveted by doctors and researchers, have hit the market, representing a

potentially powerful tool to help diagnose the devastating memory-robbing illness, which afflicts 6.5 million Americans.

The tests detect tiny amounts of abnormal proteins in the blood, including a sticky version called amyloid beta, to

determine whether the pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s are present in the brain.

“If you had asked me five years ago if we would have a blood test that could reliably detect plaques and tangles in the

brain, I would have said it was unlikely,” said Gil Rabinovici, a neurologist at the University of California at San

Francisco. “I am glad I was wrong about that.”

In coming years, the blood tests could transform the way Alzheimer’s is researched, diagnosed and treated, experts say.

Already, the tests, which are being used mostly in clinical trials, are expediting research. In regular patient care,

doctors can prescribe the tests, but that happens infrequently, in part because of a lack of effective treatments if the

tests are positive. In addition, the tests, which cost hundreds of dollars or more, often are not covered by insurance.

But many neurologists say it is a matter of time before the tests are adopted more widely, providing clarity for a

disease that is notoriously difficult to diagnose and helping determine which patients should get new treatments — if

federal regulators approve therapies now under review.

Yet the tests are stirring intense debate on scientific and ethical questions: Who should get them and when? How

accurate are they? Do patients want to know whether they have Alzheimer’s? Should people who do not have symptoms be

tested?

Some doctors remain skeptical, saying the tests are not ready for widespread use. Even many who are enthusiastic say

they want to see more data about how the tests perform given the high stakes involved.

The blood tests are emerging just as major developments in treatment may be on the horizon. In September, data showed an

experimental drug, called lecanemab, modestly slowed cognitive and functional decline. The medication, from Japanese

drugmaker Eisai and its American partner, Biogen, was the first Alzheimer’s drug to clearly slow deterioration in a

well-executed clinical trial. The data has not been peer-reviewed, and more information is expected this month. The FDA

is scheduled to decide whether to approve the drug by Jan. 6.

The lecanemab success bolstered hope for drugs that remove amyloid plaques from the brain. But in recent days, a Roche

drug failed in clinical trials, raising questions about the therapies. Results from an Eli Lilly drug are expected next

year.

If the FDA approves any of the new amyloid-busting treatments, and Medicare subsequently decides to cover them, demand

for the drugs could surge. To prescribe them, physicians would need to know whether patients have buildups of abnormal

proteins in their brains because the drugs are not risk-free: They can cause safety problems, including brain bleeding

and swelling.

“If there is a therapy that clearly demonstrates a clinical benefit, demand for these blood tests could skyrocket,” said

Reisa Sperling, director of the Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Tests and treatments for Alzheimer’s — and their futures — are inevitably intertwined, especially as the number of

people with the disease is projected to grow. Unless medical breakthroughs change the trajectory, nearly 13 million

people in the United States are expected to be living with Alzheimer’s by 2050, according to the Alzheimer’s

Association. Worldwide, the number is projected at 153 million, according to research in the Lancet.

Diagnosing Alzheimer’s is challenging, especially at earlier stages. Brain autopsies are the only way to be sure the

disease is present. Spinal taps and specialized PET scans are highly accurate at detecting biological changes —

“biomarkers” — that define the disease. But spinal taps are invasive and the scans, which can cost $5,000 or more, are

not covered by Medicare except in trials.

Most physicians rely on symptoms, cognitive tests and other assessments to diagnose Alzheimer’s. In primary care, where

most patients are evaluated, more than half are misdiagnosed, research shows.

During the last 15 years, researchers have become increasingly interested in developing blood tests that provide a

window into the brain.

Today, at least three tests — by C2N Diagnostics, Quest Diagnostics and Quanterix — are on the market in most states,

with more on the way. C2N debuted a test two years ago based on discoveries by Washington University scientists. Tests

by Quest and Quanterix entered the market this year. They all test specifically for Alzheimer’s and none is covered by

Medicare.

Other companies, including Eli Lilly and Roche, have developed tests or are working on them. Next-generation tests are

on the way. In addition, Labcorp in July began offering a test for neurodegeneration that may occur because of head

trauma or disease, including Alzheimer’s.

C2N charges $1,250 for its test and offers financial assistance for eligible patients. Quest, which charges $500, said

some health plans are paying for the test. Quanterix declined to disclose a price but said its test is much cheaper than

specialized scans. All the companies are trying to secure broader insurance coverage.

C2N and Quanterix say their tests are for patients experiencing cognitive problems. Quest says its test is for people

with or without symptoms. Many experts do not recommend using blood tests on asymptomatic individuals outside trials,

saying there has not been enough research involving that group.

Quest spokeswoman Kimberly Gorode said the company relies on physicians “to use their own discretion when ordering

tests.” She added that the company believes the test’s “clinical utility will increase” if the FDA approves new

therapies.

Jonathan D. Drake, associate director of the Alzheimer’s Disease and Memory Disorders Center at Lifespan’s Rhode Island

Hospital in Providence, used C2N tests for more than three dozen patients in a company-sponsored study. He described his

experience as positive and is cautiously optimistic, but said more data needs to be gathered before these tests become

part of routine evaluations.

Share this article

Share

“This is a brand-new technology, and it will take some time to figure out how useful it really is, in what types of

patients and under what kind of circumstances,” Drake said.

Other physicians plan to use the tests as soon as they are covered by Medicare and other insurance. Seth Keller, a

Lumberton, N.J., neurologist, said he has diagnosed Alzheimer’s the same way for 30 years — with physical examinations,

interviews, questionnaires, brain scans and memory studies — but is bothered by the uncertainty.

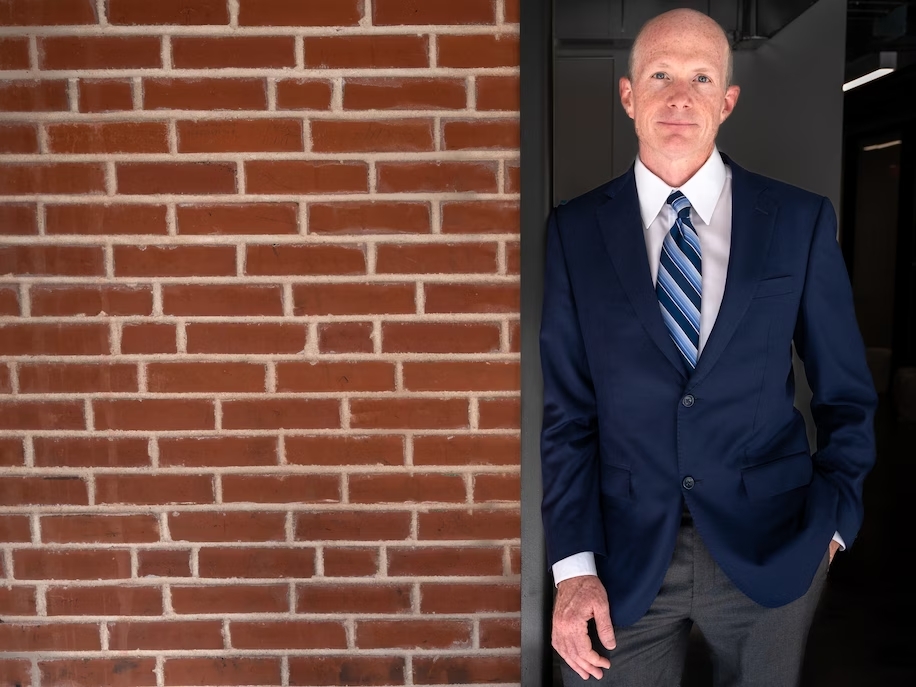

Samantha Koch, a laboratory scientist at C2N Diagnostics in St. Louis, demonstrates how plasma is processed to detect disease markers of Alzheimer’s. (Sid Hastings for The Washington Post)

Physician, test thyself

C2N, the small St. Louis biotech company that made the test used for Lynn, was founded in 2007 by two Washington University neurologists, Randall J. Bateman and David M. Holtzman, along with two physicians with experience in the life sciences industry, Joel Braunstein and Ilana Fogelman.

Physicians can order the test, called PrecivityAD, for patients 60 and older experiencing memory or other cognitive issues. The test, company officials say, is designed to complement doctors’ evaluations, not replace them.

It arrives at physicians’ offices in a shoebox-size kit equipped with a blood vial, a cold pack and instructions. After the blood is collected, it is spun in a centrifuge to separate the plasma, the yellowish liquid part that is sent back to C2N. Doctors receive results within 10 days.

On a recent day in C2N’s lab, scientist Samantha Koch prepared plasma samples for analysis by mass spectrometers, instruments that identify compounds by molecular weight. For the Alzheimer’s test, the devices detect two types of amyloid and also determine whether an individual has genetic variants that affect the risk of developing the disease.

After a patient’s age is added, an algorithm produces an “amyloid probability score” that indicates the likelihood of a patient having plaques that would show up on an amyloid PET scan, the gold standard for Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

About 10 to 15 percent of patients fall into a gray zone that requires more evaluation, Braunstein said. For the rest, results agree with the PET scans about 85 percent of the time, according to the company and studies published in April in the journal JAMA Network Open.

C2N is close to launching a new, improved version of the test, based on Washington University research, that will also detect a form of tau, a protein whose toxic tangles are linked to Alzheimer’s. The amyloid-tau combination test is 90 percent accurate, the company said, making it comparable to spinal taps and amyloid PET scans.

Eli Lilly has also developed a test that detects tau. It is using the test in clinical trials and expects a commercial launch next year, according to Mark Mintun, senior vice president of pain and neurodegeneration research and clinical development.

The improved accuracy of the next generation of tests could prompt more insurers to cover them, some experts say.

For C2N, the journey to this moment began years ago. It started, like many advances in science, with a few seemingly simple questions that Bateman, then a postdoctoral research fellow, asked Holtzman, his mentor.

Why do people — but not other mammals — get amyloid plaques in their brains? Is the protein accumulating and not being cleared?

In 2004, Bateman launched a groundbreaking experiment to measure how quickly amyloid is produced and cleared by the brain. For 36 hours, spinal catheters collected cerebrospinal fluid from several participants, some of whom had Alzheimer’s. Bateman served as his own first subject.

The study showed that Alzheimer’s patients produced amyloid beta at the same rate as other people but cleared it more slowly. Bateman theorized that the clearance rates might form the basis for a diagnostic test, but ultimately went in a different direction.

In 2017, as he prepared to speak at an international conference in London, Bateman was uncharacteristically nervous. He was about to announce a breakthrough in detecting Alzheimer’s through blood tests — something many researchers had concluded was impossible.

Highly sensitive mass spectrometry, he told the audience, detected tiny amounts of amyloid beta in the blood with unprecedented consistency and precision. By measuring two forms of the protein, scientists could develop a ratio that indicated when one type declined — a sign that plaques were accumulating in the brain.

The audience fell silent. “My first thought was they must have thought I had lost my mind,” Bateman said. It turned out they wanted to hear more.

Even before the presentation, Bateman — and other researchers in industry and academia — had started working to detect other disease markers, including tau.

Brain abnormalities develop 10 to 20 years before symptoms emerge, suggesting people might be able to take steps to delay or prevent the disease. Blood tests could alert individuals to their risks, allowing them to receive a preventive therapy, if one is developed, or pursue better exercise and diet.

“Imagine getting a blood test at age 50 or 60 and if you have amyloid plaque … we give you a drug,” Bateman said. It would be akin to a cholesterol test signaling that medication or a change in diet might reduce the risk of heart

disease.But that scenario is years away. For now, said Michael Weiner, a UCSF neurologist and radiologist, “we are at the beginning of the beginning.”

Randall J. Bateman, a Washington University neurologist and co-founder of C2N, hopes that eventually blood tests will help delay or prevent Alzheimer’s before symptoms occur. (Sid Hastings for The Washington Post)

Promise and questions

Last summer, physicians and researchers convened by the Alzheimer’s Association published an article laying out recommendations on using the blood tests. While praising the tests’ potential, they urged a cautious approach, saying that memory clinics could start using them, with confirmatory measures, but that primary-care doctors should not.

“We believe additional research is needed before they could be used as stand-alone diagnostic tests broadly in primary care,” said Rebecca M. Edelmayer, senior director for scientific engagement for the Alzheimer’s Association and a co-author of the paper, which urged that the tests be studied in more-diverse populations and in patients with medical conditions that could affect the results. Chronic kidney disease, for example, can cause false positives.

In October, another expert group, which included representatives from test companies, issued recommendations that were more upbeat, saying the tests are appropriate for primary-care settings. But the group also endorsed additional research and said the tests should not be used on people who do not have symptoms.

Oskar Hansson, an Alzheimer’s researcher at Lund University in Sweden who was the lead author of the first paper and a co-author of the second, explained the seeming contradiction regarding widespread use of the tests. He said the tests could be a critical tool in primary care but also worried the results could be misinterpreted or used in place of a comprehensive evaluation.

C2N’s Braunstein, a co-author of the second paper, said primary-care doctors could easily use the tests, as long as they are given sufficient information. He predicted concerns about the tests will fade as more data about their performance is published.

Some patients already say they are glad they got tested. When Arthur, a 72-year-old resident of Raleigh, N.C., started having memory problems, he wanted to know whether he had Alzheimer’s but could not get a spinal tap because he is on blood thinners. He got the C2N test, which showed he had a high probability of having amyloid plaques.

His wife, Nance, said that despite the concerning news, “for us, the knowledge has been a gift.”

A 77-year-old New Orleans man recently got the C2N test because of forgetfulness and daytime sleepiness. His brother, who has Alzheimer’s, no longer recognizes family members.

When the test was negative, “it relieved my apprehension and anxiety,” said the patient, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for privacy reasons. He was diagnosed with severe sleep apnea, which could partly explain his medical problems.

The right target?

The debate about the blood tests is occurring amid a long-running argument over treatments — specifically, whether removing brain amyloid can slow or stop Alzheimer’s. While the “amyloid hypothesis” has many supporters, it has yielded repeated drug failures.

Some scientists argue that amyloid might not be a cause of Alzheimer’s, merely a bystander in a neurodegenerative process, and that it is important to target tau or inflammation. Others say the recent trial success of the Eisai-Biogen drug supports the hypothesis. Results from Eli Lilly’s anti-amyloid drug may shed light on the debate.

The disagreement over amyloid hit a fever pitch last year when the FDA granted accelerated approval to a medication called Aduhelm, despite confusing effectiveness data. Studies showed the drug sharply lowered amyloid but did not prove that it slowed cognitive decline. The treatment never won broad Medicare coverage or acceptance from patients or physicians.

Demetrius M. Maraganore, chairman of the neurology department at the Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans, said that combinations of drugs ultimately will be needed to defeat Alzheimer’s.

“But we have to start someplace,” Maraganore said. “We have to create a runway. You can’t land a plane without a runway.”

January 22, 2024

January 22, 2024 By admin

By admin