Abstract

Background

Neurodegenerative disorders have been reported in elite athletes who participated in contact sports. The incidence of neurodegenerative disease among former professional soccer players has not been well characterized.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to compare mortality from neurodegenerative disease among 7676 former professional soccer players (identified from databases of Scottish players) with that among 23,028 controls from the general population who were matched to the players on the basis of sex, age, and degree of social deprivation. Causes of death were determined from death certificates. Data on medications dispensed for the treatment of dementia in the two cohorts were also compared. Prescription information was obtained from the national Prescribing Information System.

Results

Over a median of 18 years, 1180 former soccer players (15.4%) and 3807 controls (16.5%) died. All-cause mortality was lower among former players than among controls up to the age of 70 years and was higher thereafter. Mortality from ischemic heart disease was lower among former players than among controls (hazard ratio, 0.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.66 to 0.97; P=0.02), as was mortality from lung cancer (hazard ratio, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.70; P<0.001). Mortality with neurodegenerative disease listed as the primary cause was 1.7% among former soccer players and 0.5% among controls (subhazard ratio [the hazard ratio adjusted for competing risks of death from ischemic heart disease and death from any cancer], 3.45; 95% CI, 2.11 to 5.62; P<0.001). Among former players, mortality with neurodegenerative disease listed as the primary or a contributory cause on the death certificate varied according to disease subtype and was highest among those with Alzheimer’s disease (hazard ratio [former players vs. controls], 5.07; 95% CI, 2.92 to 8.82; P<0.001) and lowest among those with Parkinson’s disease (hazard ratio, 2.15; 95% CI, 1.17 to 3.96; P=0.01). Dementia-related medications were prescribed more frequently to former players than to controls (odds ratio, 4.90; 95% CI, 3.81 to 6.31; P<0.001). Mortality with neurodegenerative disease listed as the primary or a contributory cause did not differ significantly between goalkeepers and outfield players (hazard ratio, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.43 to 1.24; P=0.24), but dementia-related medications were prescribed less frequently to goalkeepers (odds ratio, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.19 to 0.89; P=0.02).

Conclusions

In this retrospective epidemiologic analysis, mortality from neurodegenerative disease was higher and mortality from other common diseases lower among former Scottish professional soccer players than among matched controls. Dementia-related medications were prescribed more frequently to former players than to controls. These observations need to be confirmed in prospective matched-cohort studies. (Funded by the Football Association and Professional Footballers’ Association.)

Introduction

QUICK TAKE

QUICK TAKE

Neurodegenerative Disease Mortality and Former Professional Soccer Players

01:47

Concerns have been raised about the risk of several neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), associated with participation in contact sports.1-3 Recognition of the pathologic changes of CTE in former players who participated in a range of contact sports,4-8 including American football4,5 and soccer,6,9-13 has partly led to these concerns. Data regarding the risk of neurodegenerative disease among former professional soccer players are limited.

The neurocognitive consequences of participation in contact sports are uncertain, but the overall health benefits of physical activity in the prevention of chronic diseases, including dementia,14 and in the reduction in mortality15,16 have been established. Studies have also shown that participants in elite-level sports have evidence of lifelong health benefits,17 including lower all-cause mortality18 and lower risk of cardiovascular disease19 than the general population.

Soccer is played in over 200 countries by more than a quarter of a billion people.20 Although casual and amateur play is not comparable to professional soccer, information on health outcomes among former professional players may be valuable to inform the management of risks in the sport. We conducted a retrospective cohort study to compare mortality from neurodegenerative disease among Scottish former professional soccer players with that among matched controls from the general population.

Methods

Study Oversight

This study was approved by the College of Medical, Veterinary, and Life Sciences Ethics Committee, University of Glasgow. The protocol, which has been previously published,21 and data-governance procedures were reviewed and approved by National Health Service (NHS) Scotland Public Benefit and Privacy Panel for Health and Social Care. All data from health records were deidentified by an independent information analyst who worked in the electronic Data Research and Innovation Service of NHS Scotland; participant-level consent was not required. The results from this study were analyzed and reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.22 The authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and for the fidelity of the study to the protocol.

Inclusion Criteria

We accessed electronic health records to obtain data on death certification and medications that are typically prescribed for the treatment of dementia in a cohort of former professional soccer players. Former professional soccer players were identified from databases of all Scottish professional soccer players23,24 that were compiled from the archives of the Scottish Soccer Museum and the individual league clubs. Available data included the full name and date of birth of the players and career information, including dates of first signing and retirement, number of match appearances, and player position. These databases were merged, and duplicate entries deleted. Persons born before January 1, 1977, were eligible for inclusion in the study. All the former soccer players were male.

Probabilistic matching was applied to the full name and date of birth of former soccer players to link them to their unique Community Health Index numbers. Variables such as date of birth and full name were compared between former players and Community Health Index data sets, and a score was attached to each matched variable that reflected the level of agreement. The scores for each variable were summed to generate an overall score, which correlated with the likelihood of the two records belonging to the same person. An automated computer program was used to match former players with controls from the general population, in a 1:3 ratio, on the basis of sex, year of birth, and degree of social deprivation. To match the degree of social deprivation between cohorts, we used records from the NHS Information Services Division, which contain the last known postal code of residence for all persons. For each area of residence, data on social deprivation were derived with the use of postal code–level data on income, employment, health, education, housing, access to local amenities, and crime and were categorized into quintiles on the basis of the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD), with the quintiles ranging from 1 (most deprived) to 5 (least deprived).25

The Community Health Index number can be linked to death certificates and records in the national Prescribing Information System. Information recorded on death certificates includes the date of death and the primary and contributory causes of death, coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision and 10th Revision (ICD-9 and ICD-10). The Prescribing Information System documents every prescription dispensed in the community and has included complete Community Health Index data since 2009; medications are coded according to the British National Formulary.26 The ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes that were used to identify outcomes as death with neurodegenerative disease listed as the primary or a contributory cause (classified as all neurodegenerative diseases, dementia not otherwise specified, Alzheimer’s disease, non-Alzheimer’s dementias, motor neuron disease, and Parkinson’s disease) and the remaining most common causes of death in the Scottish adult male population (diseases of the circulatory system [classified as all diseases of the circulatory system, ischemic heart disease, and stroke or cerebrovascular disease], diseases of the respiratory system, or cancer [classified as any cancer or lung cancer]) are provided in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. Because no ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes exist for CTE or its synonym, dementia pugilistica, these diagnoses were not identifiable from death certificate records. The medications included in the analysis of medications for dementia are listed in Section 4.11 of the British National Formulary and in Table S2. All analyses included data up to December 31, 2016, and the database interrogation was performed on December 10, 2018.

Statistical Analysis

We used Cox proportional-hazards regression to model time to death and Schoenfeld residuals to test the assumption of proportional hazards.27 When the assumption of proportional hazards did not hold, a time-varying model was used to derive hazard ratios over different periods of follow-up.28 Age was used as the time covariate, with follow-up from age 40 years to the date of data censoring, which was either the date of death or the end of follow-up (December 31, 2016), whichever occurred first. In a sensitivity analysis, the outcome of death from neurodegenerative disease was subjected to a competing-risks regression analysis to ascertain whether the estimated hazard ratio was sensitive to the competing risks of death from ischemic heart disease and death from any cancer.29 We tested the assumption of proportional subhazards (hazard ratios adjusted for competing risks of death from ischemic heart disease and death from any cancer) by including an interaction term between time of analysis and a dummy variable for former soccer player status and assessing whether the interaction was significant (P<0.05). The mortality models were repeated in the analysis of the subgroups of former players defined according to player position (outfield player or goalkeeper). Because prescribing outcomes were available only from 2009 onward, we applied a nested case–control design in which conditional logistic regression was used to analyze the whole cohort (matched data)30 and standard logistic regression was used to analyze the subgroups of former players defined according to player position. All statistical analyses were performed with the use of Stata/MP software, version 14.1 (StataCorp). Two-sided P values of less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Study Cohorts

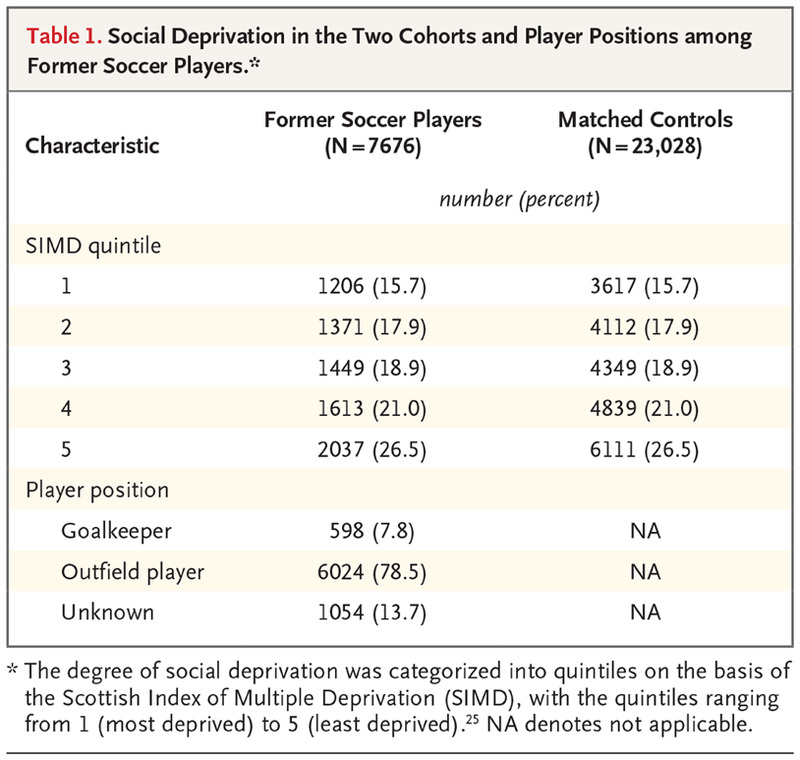

Social Deprivation in the Two Cohorts and Player Positions among Former Soccer Players.

A total of 9670 records of former professional soccer players were identified from the player databases; 7676 of the 9670 records were successfully matched to Community Health Index numbers, which permitted the identification of 23,028 matched controls (Table 1). The remaining 1994 records could not be matched to a Community Health Index number because of duplicate entries (170 records) or incomplete or inaccurate demographic information (1824 records) (Fig. S1). During a median follow-up of 18.0 years from study entry at the age of 40 years, 1180 former soccer players (15.4%) and 3807 matched controls (16.5%) died; the mean (±SD) age at death was 67.9±13.0 years and 64.7±14.0 years, respectively.

Primary Cause of Death

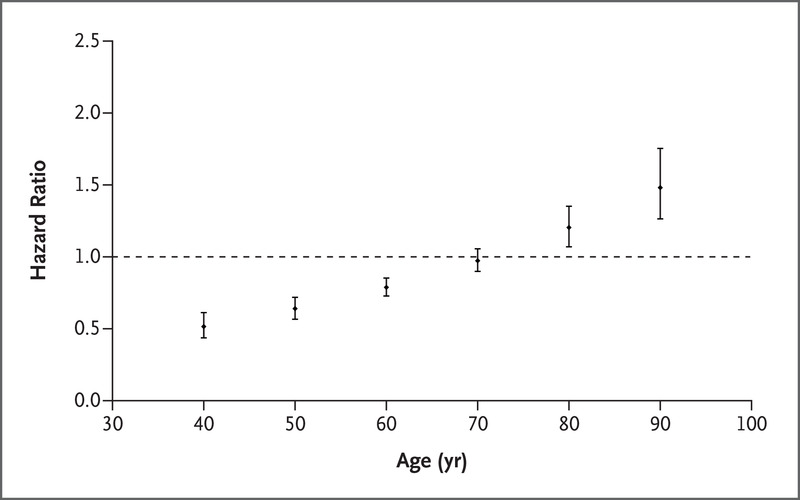

Time-Varying Hazard Ratios for Death from Any Cause among Former Soccer Players 40 to 90 Years of Age, as Compared with Matched Controls.

Because the proportional-hazards assumption did not hold for all-cause mortality when former professional soccer players were compared with matched controls from the general population, a time-dependent analysis was performed. This analysis showed that all-cause mortality was lower among former professional soccer players up to the age of 70 years and was higher thereafter. Time-varying hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated with the use of the “lincom” command in Stata software.

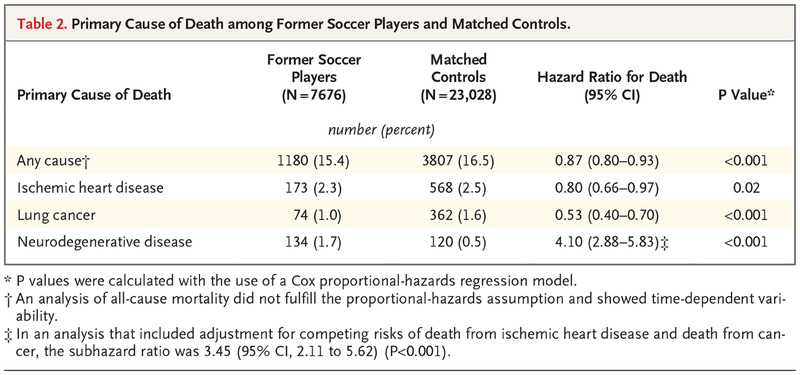

Primary Cause of Death among Former Soccer Players and Matched Controls

All-cause mortality was lower among former soccer players than among matched controls (hazard ratio, 0.87; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.80 to 0.93; P<0.001); however, the proportional-hazards assumption was not met. A time-dependent analysis showed that mortality was lower among former soccer players than among matched controls up to the age of 70 years and was higher thereafter (Figure 1). The analyses of death from ischemic heart disease (hazard ratio [former players vs. matched controls], 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66 to 0.97; P=0.02) and death from lung cancer (hazard ratio, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.70; P<0.001) fulfilled the proportional-hazards assumption and showed that mortality from either of these causes was lower among former soccer players than among matched controls (Table 2).

Mortality with neurodegenerative disease listed as the primary diagnosis on the death certificate was 1.7% among former soccer players and 0.5% among matched controls (hazard ratio, 4.10; 95% CI, 2.88 to 5.83; P<0.001), but after adjustment for the competing risks of death from ischemic heart disease and death from any cancer, this higher mortality was partially attenuated (subhazard ratio, 3.45; 95% CI, 2.11 to 5.62; P<0.001) (Table 2). Mortality from stroke or cerebrovascular disease did not differ significantly between study cohorts (hazard ratio, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.78 to 1.00; P=0.06). Analyses of death from any cancer (hazard ratio, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.71 to 1.25) and death from respiratory disease (hazard ratio, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.46 to 0.82) did not meet the proportional-hazards assumption.

Neurodegenerative Causes of Death and Prescriptions of Dementia-Related Medications

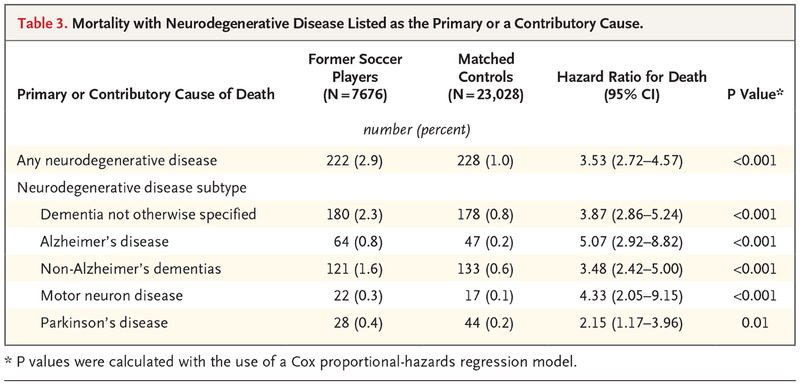

Mortality with Neurodegenerative Disease Listed as the Primary or a Contributory Cause.

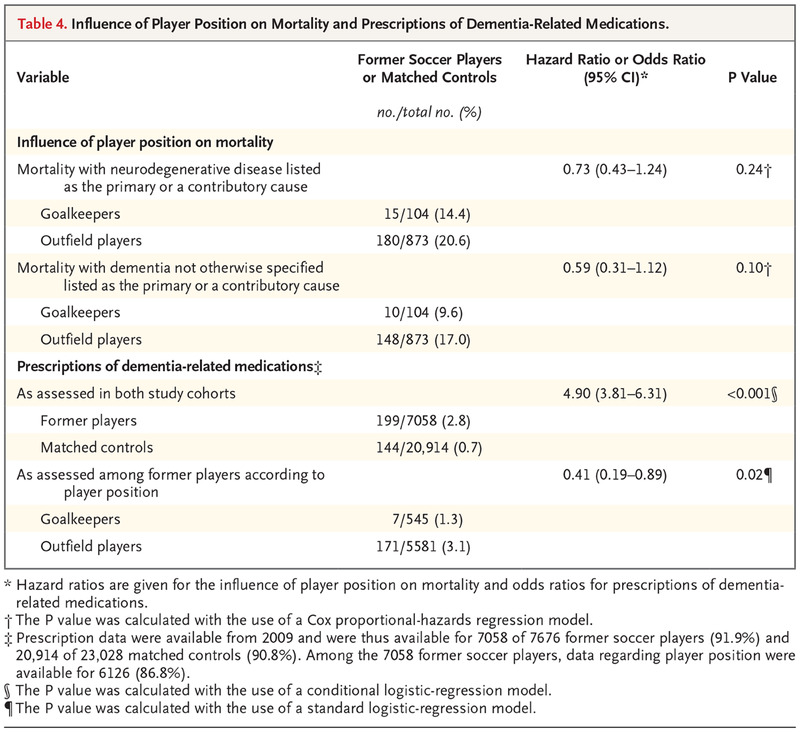

Influence of Player Position on Mortality and Prescriptions of Dementia-Related Medications.

Neurodegenerative disease was recorded as the primary or a contributory cause of death in 222 former soccer players (2.9%) and 228 matched controls (1.0%) (hazard ratio, 3.53; 95% CI, 2.72 to 4.57; P<0.001). Among former players, the estimated risk of death with neurodegenerative disease listed as the primary or a contributory cause varied according to disease subtype (Table 3) and was highest for those with Alzheimer’s disease (hazard ratio, 5.07; 95% CI, 2.92 to 8.82; P<0.001) and lowest for those with Parkinson’s disease (hazard ratio, 2.15; 95% CI, 1.17 to 3.96; P=0.01). Age at death with neurodegenerative disease or its subtypes listed as the primary or a contributory cause did not differ significantly between former soccer players and matched controls, other than for non-Alzheimer’s dementia (77.5±7.5 years of age [former players] vs. 81.3±7.3 years of age [controls]; P=0.005) (Fig. S2). Former soccer players were more likely to receive a prescription of a dementia-related medication than matched controls (odds ratio, 4.90; 95% CI, 3.81 to 6.31; P<0.001) (Table 4).

Influence of Player Position on Mortality and Prescriptions of Dementia-Related Medications

In the subgroup analysis based on player positions, mortality with neurodegenerative disease listed as the primary or a contributory cause on the death certificate did not differ significantly between goalkeepers and outfield players (hazard ratio, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.43 to 1.24; P=0.24). Similarly, there was no significant difference between those groups when the primary or contributory cause was listed as dementia not otherwise specified (hazard ratio, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.31 to 1.12; P=0.10) (Table 4). Dementia-related medications were prescribed less frequently to goalkeepers than to outfield players (odds ratio, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.19 to 0.89; P=0.02) (Table 4).

Discussion

Our data show that all-cause mortality was lower in a cohort of Scottish former professional soccer players than in a control cohort of adults from the general population who were matched to the players on the basis of sex, age, and degree of social deprivation. This association was age-dependent; mortality was lower among former soccer players up to the age of 70 years and was higher thereafter. Mortality with neurodegenerative disease listed as the primary diagnosis on the death certificate was higher among the former soccer players than among the controls, a finding that was independent of the competing risks of death from ischemic heart disease and death from cancer; however, when these competing risks were incorporated into the analysis, this higher mortality was partially attenuated. Among the former players, the estimated risk of death with neurodegenerative disease listed as the primary or a contributory cause was highest for those with Alzheimer’s disease and lowest for those with Parkinson’s disease. These observations are consistent with our finding that dementia-related medications were prescribed more frequently to former players than to controls. Mortality with neurodegenerative disease listed as the primary or a contributory cause did not differ significantly between outfield players and goalkeepers; however, dementia-related medications were prescribed more frequently to outfield players.

The observation of a lower all-cause mortality up to the age of 70 years among former professional soccer players is similar to findings in previous studies involving elite athletes who participated in a range of sports,17 including soccer,31 and may reflect higher levels of physical activity and lower levels of obesity and smoking in elite athletes than in the general population. In contrast, mortality from neurodegenerative disease was higher among former soccer players, a finding consistent with studies involving former players in the U.S. National Football League.18,32 Neither CTE nor dementia pugilistica was a coded item in ICD-9 or ICD-10, and it was not possible to inquire about these causes of death in our study. Studies reporting clinicopathological diagnoses from autopsies in former soccer players show a range of dementia subtypes. In some series, neuropathologic changes consistent with CTE have been described as occurring in 75% of former soccer and rugby players; however, such changes were infrequently the primary pathologic cause of dementia.13 Because of the lack of specific diagnostic coding for CTE, we were unable to make conclusions regarding its presence as either the primary diagnosis or a coexisting disease, but it may have been coded among other disorders, if diagnosed.

Death certificates are subject to errors in reporting. We sought to corroborate our findings on mortality from neurodegenerative disease and dementia by investigating the proportions of persons who received prescriptions of medications that are typically used for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. The findings from this analysis, showing that dementia-related medications were prescribed more frequently to former soccer players than to controls, supported the observations made from the comparison of death certificates.

A strength of this study was the inclusion of a comprehensive cohort of former Scottish professional soccer players. We compared the outcomes in this cohort with those of matched controls from the general population and adjusted our estimates for competing causes of death when calculating the risk of death from neurodegenerative causes. However, not all former players identified from the master data sets of professional soccer players could be matched to Community Health Index numbers. It is possible that differences between this group of players who could not be matched and the former players who were included in the study introduced bias into our results. The relevance of our findings in elite athletes to recreational soccer participation is not known. These observations cannot be applied directly to recreational and amateur soccer players.

In summary, our data show that mortality from neurodegenerative disease was higher and prescriptions of dementia-related medications were more common among former professional soccer players than among controls from the Scottish population. The risk of death from neurodegenerative disease varied according to disease subtype. Mortality from other common diseases was lower among former soccer players than among controls. These data need to be confirmed in prospective matched-cohort studies.

Funding and Disclosures

Supported by the Football Association and Professional Footballers’ Association and by an NHS Research Scotland Career Researcher Fellowship (to Dr. Stewart).

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

This article was published on October 21, 2019, and updated on November 7, 2019, at NEJM.org.

Author Affiliations

From the Institute of Health and Wellbeing (D.F.M., J.P.P.), the Institute of Neuroscience and Psychology (E.R.R., W.S.), and the Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences (K.S., J.A.M.), University of Glasgow, the Hampden Sports Clinic, Hampden Stadium (K.S., J.A.M.), and the Department of Neuropathology, Queen Elizabeth University Hospital (W.S.) — all in Glasgow, United Kingdom.

Address reprint requests to Dr. Stewart at the Department of Neuropathology, Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, 1345 Govan Rd., Glasgow G51 4TF, United Kingdom, or at william.stewart@glasgow.ac.uk.

Supplementary Material

| Supplementary Appendix | 467KB | |

| Disclosure Forms | 123KB |

October 27, 2023

October 27, 2023 By admin

By admin